Prior Knowledge and long-term memory.

Abstract

The working mechanism of human memory is quite complex. It is fascinating to know how information from the memory is processed, stored, and retrieved. Long-term memory is further divided into declarative memory, which comprises episodic and semantic memory, and procedural memory (Tulving, 1972). In this paper, we’ll try to understand in detail how long-term memory operates – representation, activation, and retrieval of information from long-term memory. The paper then elaborates on the relation between the process of learning and prior knowledge. Further, the paper discusses the role of recency and frequency in information retrieval from long-term memory. Later we will emphasize the sub-theme of ‘categorization’ and ‘metaphor’ to review the design of Axure, a wireframing and prototyping tool.

1. Knowledge representation

Various theories were proposed for symbolic representation of the knowledge stored in long-term memory. Schema, scripts, frames and mental models are used to represent knowledge as structured networks, whereas semantic and proposition networks are used to represent knowledge as interconnected networks. These knowledge representation theories are discussed in the following sections.

1.1. Knowledge representation as a structured network

The schema theory was first proposed by Sir Frederic Charles Bartlett (1886–1969) in 1933. (Bartlett, & Burt, 1933) While experimenting with the recall of Native American folktales, Bartlett observed that many recalls were not exact. Subjects substituted unfamiliar information with facts they already knew. In order to classify this inaccuracy of memory, Bartlett proposed the schema theory. According to his theory, human beings store information in the form of unconscious mental structures called schema (plural: schemata) and that these schemata, upon interaction with new information, create inaccuracy in a recall. Thus, the schema can be viewed as a highly structured and active organization of past knowledge, which is stored in long-term memory that influences new information (Bartlett, & Burt, 1933). (DiMaggio, 1997) This organization of schemata maintains order upon the long-term memory. Apart from representations of knowledge, schemata are also information processing mechanisms that simplify cognition (DiMaggio, 1997). Abelson described script as a type of schema that represents a mundane or typical sequence of events (Abelson, 1981).

(Minsky 1974) further elaborated the schema theory by suggesting the concept of frames for structure-based representation of knowledge. Minsky explained that frames are composed of slots that accept a range of values, and if the value is not present, a default value is filled in. Frames provided visual context for a top-down rendition of where to look and what to look for (Minsky 1974).

Kenneth Craik (1943) (as cited in Johnson-Laird et al., 1998) wrote that “the mind constructs ‘small-scale models’ of reality that it uses to anticipate events, to reason, and to underlie explanation”. (Johnson-Laird, 1983) Mental Models are

defined as mental representations of a knowledge structure that helps understand certain facts, events or situations. Johnson-Laird explained that humans build mental models on the understanding of their description of the world and their knowledge.

The built model is very similar to the actual world but less detailed (Johnson-Laird, 1983). Norman described mental model as “People’s view of the world, of themselves, of their own capabilities, and of the tasks that they are asked to perform,

or topics they are asked to learn, depend heavily on the conceptualizations that they bring to the task” (Norman, 1983). He made some core observations about mental models:

1. They are not complete.

2. People’s capability to process their

models are limited.

3. They are unstable. Details are forgotten especially if they haven’t been used for a while.

4. They do not have firm boundaries. Similar devices, operations get confused.

5. They are unscientific.

6. They

are parsimonious. People often put more physical effort than mental.

He also stated that a mental model is naturally evolving based on the person’s experience and background.

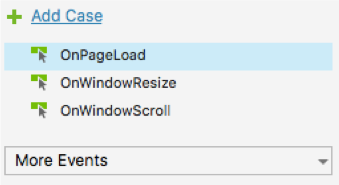

Taking the case of Axure, the interaction session, as shown in figure 1, does not represent the users’ mental model. The terminology used for interaction does not represent the user’s belief system. Users of Axure are designers who see interactions as actions and not events. The terminology ‘events’ fits well with developers’ mental model. Likewise, terminology ‘case’ is used by developers. I would suggest replacing ‘events’ and “case’ 'by ‘interactions’ and ‘conditions’ respectively.

Figure 1

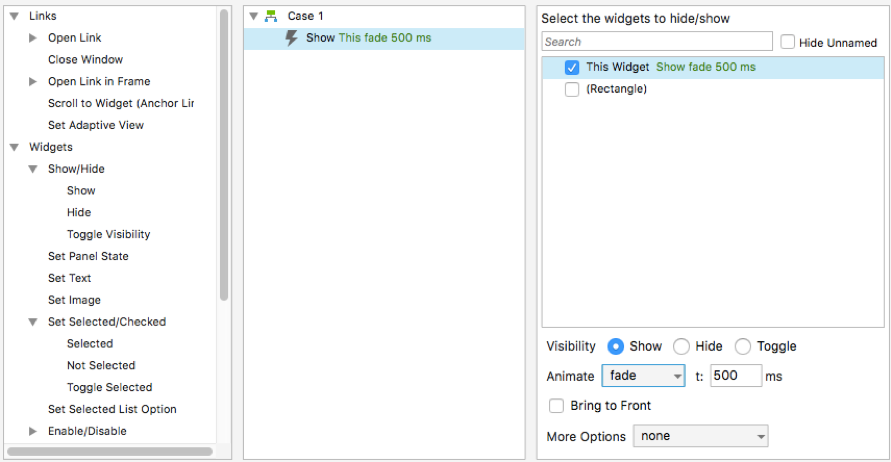

However, the mechanism to add an interaction in Axure does match the user’s mental model. The User’s model of interaction is somewhat like this: ‘if a button is clicked (action), the panel must disappear (reaction) by sliding out from the bottom (animation). Accordingly, as shown in figure 2, to add an interaction in Axure, the user must first select an action (click, swipe, etc.) then select the reaction (show, hide, etc.) followed by animation (slide, fade, etc.).

Figure 2

1.2. Knowledge representation as an interconnected network

(Quillian, 1963) proposed semantic networks as a means to represent, store, and process conceptual information in computers. This theory suggests that human memory is represented as semantic networks that can be viewed either as directed or undirected graphs comprising of interconnected nodes. Nodes refer to concepts and links refer to the semantic relationship between these concepts (Quillian, 1963). (Collins, 1975) Collins broadened Quillian’s semantic network notion. According to his theory, when a concept is processed, activation spreads out from the source node and weakens as it travels away. This separates irrelevant nodes from the relevant ones. Activation from a node is released continuously at a fixed rate until a concept is processed. While activation starts at one node, it travels in parallel from other encountered nodes. He also suggested that activation has a threshold level and it would decrease over time (Collins, 1975).

(Anderson, & Bower, 1972) proposed the proposition network theory. Similar to semantic network theory, proposition network theory, too, suggests that human memory is a huge interconnected network of a huge number of nodes and links. However, according to this theory, there are two types of nodes – concepts and propositions. Propositions represented as round nodes. Each proposition or round node signifies a single fact. Links connect the concepts to propositions thus referring to the relations between the concepts (Anderson, & Bower, 1972). (Anderson, 1974) Anderson further explained that when a stimulus is processed, activation is released from all the concepts present in the stimulus. The released activation can spread in any direction along the link. As these released activations intersect, facts are recognized. However, apart from the intersection, recognition of fact also depends on the condition that the activation must reach certain threshold value (Anderson, 1974).

2. Constantly modifying memory and learning

(Mayer, 1981) Learning is adding new information to the existing network of prior knowledge. When an incoming stimulus is processed, it is assimilated to the existing network or networks of that stimulus (Mayer, 1981). This shows that long-term memory is dynamic and is continuously modified as it adjusts to the new information. The learning ability of humans is based on three factors: Structure of the material being learned; prior knowledge of the subject being learned which is nothing but the existing network structures; and the amount of activation released in the existing network throughout the learning process (Mayer, 1977).

3. Information retrieval

(Anderson, 1983) Anderson conducted experiments where subjects were asked to recall information from studied facts, real-world facts, and pictorial material. The experiment confirmed that relative frequency plays an important role in information retrieval. Subjects could make relatively rapid decisions when asked to recall information regarding facts that were studied more number of times. (Baddeley, & Hitch, 1993) Likewise, Baddeley and Hitch showed that recency effects, too, can be observed in long-term memory and further explained that recall is based on most recent experiences ranging from a few seconds to months.

Figure 3: left - Axure font list, right – Recently and frequently used fonts are displayed on top of the font list

As seen in figure 3 (left), In Axure, recently or frequently used fonts are not saved. Every time a new instance is added, the user is required to recall all the fonts that are being used in the project and then recognize the recalled fonts from the list containing all the fonts. According to (Gillund, &, Shiffrin, 1984) activation due to context and member cues are used in recall model for sampling and in recognition model for making decisions. As shown in figure 3 (right), Axure can display recently and frequently used fonts at the top of the font list.

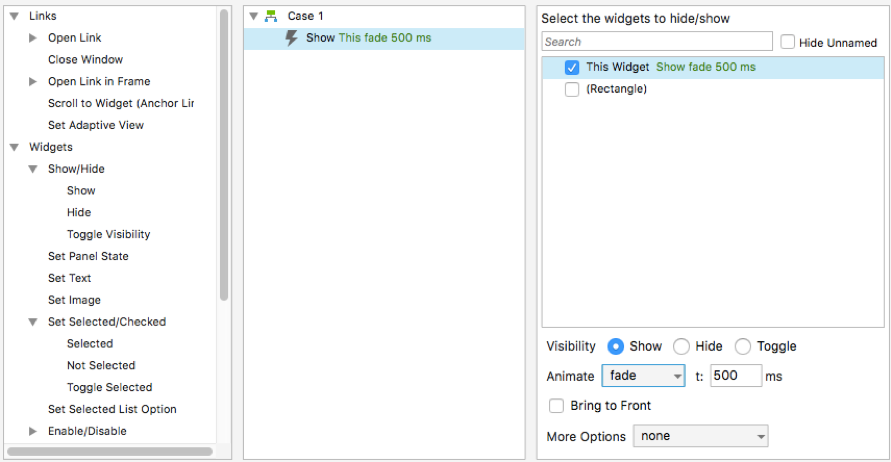

4. Categorization

(Cohen, 1987) explained that structures of knowledge or schemata, as explained earlier, are interrelated and connected into categories which amplify the efficiency of processing information. This networks or structures of knowledge enables us to recognize the incoming stimuli and react accordingly with respect to their categories. However, he did observe a few information processing issues in categorization. To point out these issues, Cohen discusses the categorization theories proposed by Smith and Medin (Cohen, 1987). (Smith, & Medin, 1981) discussed three primary theories or views of categorization as:

Classical: Entities having a certain essential set of characteristics qualify as a member of the category, while those lacking even one of the characteristics does not qualify as a member. In other words, these essential set of characteristics establish necessary and sufficient conditions to gain category membership.

Figure 4

Prototype: According to this theory, membership to a specific category does not completely rely on necessary and sufficient conditions. Entities can be grouped based on its prototypes or samples. As shown in figure 4, Axure uses the prototype view to categorize interactions. Few samples from the list of actions are displayed which enables users to draw general inference about the category and its members. For example, category ‘show/hide’ indicates that it will have ‘select’, ‘hide’ and ‘toggle visibility’ as its members and likewise category ‘selected/checked’ will have ‘check’, ‘uncheck’ and ‘toggle check’ as its members.

Figure 5

Exemplar: According to this theory, an entity is classified as a member of a category if it is similar to the concrete exemplars of that category. This is because a category’s mental representation comprises exemplars that make up the category. As shown in figure 5, Axure does a good job of grouping font types and weights using the exemplar view. ‘Arial’ and ‘Regular’ are strong examples of font types and weights respectively, which makes it easy to understand that the category of the dropdowns in spite of the missing labels.

(Dopkins, & Gleason. 1997) conducted experiments to compare exemplar and prototype theories. Results from the experiments favored exemplar over the prototype.

5. Metaphor

(Lakoff, & Johnson, 1980) described metaphor as "...a pervasive mode of understanding by which we project patterns from one domain of experience in order to structure another domain of a different kind." Metaphors help users connect conceptual entities, attributes, relations, and structures from one domain to another. (Gentner, 1988) proposed a formal theory of metaphors as a mapping between network structures of the source and network structures of the target. Thus, metaphors are a way of identifying shared relations between objects without noticing the individual to which those relations apply.

Figure 6

Axure uses the concept of metaphor quite effectively. As shown in figure 6 - left, Axure uses a ‘pen’ icon to represent the feature of creating freehand shapes, drawing an analogy from real life of using a pen or pencil to draw. Similarly, as shown in figure 6 - right, a ‘cloud’ icon is used to indicate that projects can be shared on the cloud.

6. Conclusion

Long-term memory is highly structured, intricately interconnected, and constantly modified. To build an enhanced user experience, it is imperative to understand how knowledge is stored in long-term memory; how information is retrieved from this structured and interconnected memory; how learning and information processing is affected by prior knowledge; how information or entities are categorized; and how metaphors are used to draw analogies from real life.

References

Abelson, R. P. (1981). Psychological status of the script concept. American psychologist, 36(7), 715.

Anderson, J. R., & Bower, G. H. (1972). Recognition and retrieval processes in free recall. Psychological review, 79(2), 97.

Anderson, J. R. (1974). Retrieval of propositional information from long-term memory. Cognitive psychology, 6(4), 451-474.

Anderson, J. R. (1983). Retrieval of information from long-term memory. Science, 220(4592), 25-30.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1993). The recency effect: Implicit learning with explicit retrieval?. Memory & Cognition, 21(2), 146-155.

Bartlett, F. C., & Burt, C. (1933). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 3(2), 187-192.

Cohen, J. (1987) Alternative Models of Categorization: Toward a Contingent Processing Framework.

Collins, A. M., & Loftus, E. F. (1975). A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological review, 82(6), 407.

DiMaggio, P. (1997). Culture and cognition. Annual review of sociology, 23(1), 263-287.

Dopkins, S., & Gleason, T. (1997). Comparing exemplar and prototype models of categorization. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale, 51(3), 212.

Gentner, D. (1988). Metaphor as structure mapping: The relational shift. Child development, 47-59.

Johnson-Laird, P. N., Girotto, V., & Legrenzi, P. (1998). Mental models: a gentle guide for outsiders. Sistemi Intelligenti, 9(68), 33.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by.

Mayer, R. (1977). The Sequencing of Instruction and the Concept of Assimilation-to-Schema. Instructional Science 6, 369-388.

Mayer, R. E. (1981). The psychology of how novices learn computer programming. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 13(1), 121-141.

Minsky, M. (1974). A framework for representing knowledge.

Norman, D. A. (1983). Some observations on mental models. Mental models, 7(112), 7-14.

Quillian, R. (1963). A notation for representing conceptual information. An application to seamantics and mechanical English paraphrasing (No. SP1395). SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT CORP SANTA MONICA CALIF.

Shiffrin, R. M., & Atkinson, R. C. (1969). Storage and retrieval processes in long-term memory. Psychological Review, 76(2), 179.

Smith, E. E., & Medin, D. L. (1981). Categories and concepts (p. 89). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. Organization of memory, 1, 381-403.